|

Page < 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 >

Famines

in British India: An enduring

disaster of the Raj

In 1901, shortly before the death of

Queen Victoria, the radical writer William Digby

looked back to the 1876 Madras famine and confidently asserted: "When the

part played by the British Empire in the 19th century is regarded by the

historian 50 years hence, the unnecessary deaths of millions of Indians would be

its principal and most notorious monument." Who now remembers the Madrasis?

In

the 19th century, however, drought was treated, particularly by the English in

India, as an opportunity for reasserting sovereignty.

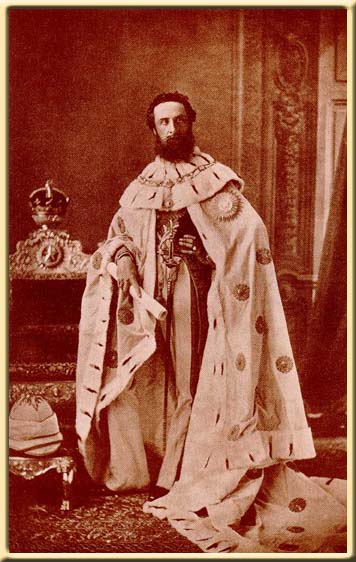

During

1876 Lord Lytton, widely suspected to be

insane, ignored all efforts to alleviate the suffering of millions of peasants

in the Madras region and concentrated on preparing for Queen

Victoria's investiture as Empress of India. The highlight of the

celebrations was a week-long feast of lucullan excess at which 68,000

dignitaries heard her promise the nation "happiness, prosperity and

welfare". During

1876 Lord Lytton, widely suspected to be

insane, ignored all efforts to alleviate the suffering of millions of peasants

in the Madras region and concentrated on preparing for Queen

Victoria's investiture as Empress of India. The highlight of the

celebrations was a week-long feast of lucullan excess at which 68,000

dignitaries heard her promise the nation "happiness, prosperity and

welfare".

(For more on Lord Lytton:

India's Nero - Please refer to

chapter on Glimpses).

Traditional Indian polities like the Moguls and

the Marathas had

zealously policed the grain trade in the public interest, distributing free

food, fixing prices and embargoing exports. As one horrified British

writer discovered, these 'oriental despots' sometimes

punished traders who short-changed peasants during famines by amputating

equivalent weights of merchant flesh.

The British worshipped a savage god known as the

'Invisible Hand' that forbade state interference in the grain trade. Like

previous viceroys (Lytton in 1877 and Elgin in 1897), Lord

Curzon allowed food surpluses to be exported to England or hoarded by

speculators in heavily guarded depots. Curzon, whose appetite for viceregal pomp

and circumstance was legendary, lectured starving villagers that 'any government

which imperiled the financial position of India in the interests of prodigal

philanthropy would be open to serious criticism; but any government which by

indiscriminate alms-giving weakened the fibre and demoralised the self-reliance

of the population, would be guilty of a public crime'.

Lord Curzon as a celebration of imperialist

ideals, even forbade the singing of a particular hymn because it contained an

inappropriate reminder of that kingdoms "may rise and wane."

(source: Colonial

Overlords: Time Frame Ad 1850-1900 -

Time-Life Books. The Scramble for Africa p. 33).

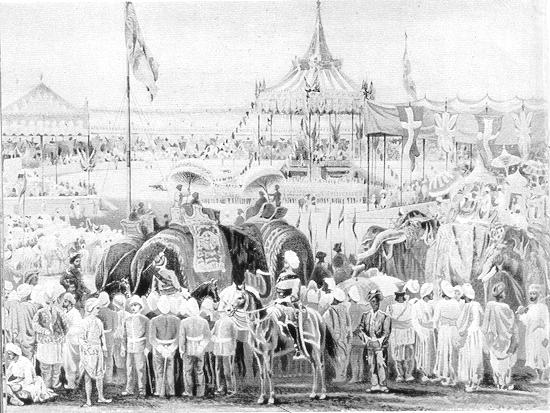

The empire had its circumstance

to impress the native princes and people. At Delhi in 1877, a great display was

made to announce the queen's assumption of the title of Empress of India.

(image source: Bound to Exile - By Michael Edwardes).

***

Vaughan Nash of the Manchester Guardian and Louis

Klopsch of the New York Christian Herald were appalled by Curzon's 'penal

minimum' ration (15 ounces of rice for a day's hard labour) as well as the

shocking conditions tolerated in the squalid relief camps, where tens of

thousands perished from cholera.

'Millions of flies,'

wrote Klopsch, 'were permitted undisturbed to pester the unhappy victims. One

young woman who had lost every one dear to her, and had turned stark mad, sat at

the door vacantly staring at the awful scenes around her.'

Famine: Victims of the 1876-77. Famine awaits death.

(image source: Raj: the Making and Unmaking of British India - by Lawrence

James).

***

Despite

Kiplingesque myths of heroic benevolence, official attitudes were nonchalant.

British officials rated Indian ethnicities like cattle, and vented contempt

against them even when they were dying in their multitudes.

Asked to

explain why mortality in Gujarat was so high, a district officer told the famine

commission: 'The Gujarati is a soft man... accustomed to earn his good food

easily. In the hot weather, he seldom worked at all and at no time did he form

the habit of continuous labour. Very many even among the poorest had never taken

a tool in hand in their lives. They lived by watching cattle and crops, by

sitting in the fields to weed, by picking cotton, grain and fruit, and by...

pilfering.'

Lytton believed in free trade. He did nothing to

check the huge hikes in grain prices, Economic "modernization" led

household and village reserves to be transferred to central depots using

recently built railroads. Much was exported to England, where there had been

poor harvests. Telegraph technology allowed prices to be centrally co-ordinated

and, inevitably, raised in thousands of small towns. Relief funds were scanty

because Lytton was eager to finance military campaigns in Afghanistan.

Conditions in emergency camps were so terrible that some peasants preferred to

go to jail. A few, starved and senseless, resorted to cannibalism. This was all

of little consequence to many English administrators who, as believers in

Malthusianism, thought that famine was nature's response to Indian

over-breeding.

It

used to be that the late 19th century was celebrated in every school as the

golden period of imperialism. While few of us today would defend empire in moral

terms, we've long been encouraged to acknowledge its economic benefits. Yet, as

Davis points out, "there was no increase in India's per capita income from

1757 to 1947". It

used to be that the late 19th century was celebrated in every school as the

golden period of imperialism. While few of us today would defend empire in moral

terms, we've long been encouraged to acknowledge its economic benefits. Yet, as

Davis points out, "there was no increase in India's per capita income from

1757 to 1947".

As the great Indian political economist Romesh

Chunder Dutt pointed out in one of his Open Letters to Lord Curzon British

Progress was India's Ruin. The railroads, ports and canals

which enthused Karl Marx in the 1850s were for resource extraction, not

indigenous development. The taxes that financed the railroads and the

Indian army pauperised the peasantry. Not surprisingly, there was no increase in

India's per capita income during the whole period of British overlordship from

1757 to 1947. Celebrated cash-crop booms went hand in hand with declining

agrarian productivity and food security. Moreover, two decades of demographic

growth (in the 1870s and 1890s) were entirely wiped out in avoidable famines,

while throughout that 'glorious imperial half century' from 1871 to 1921

immortalised by Kipling, the life expectancy of ordinary Indians fell by a

staggering 20 per cent.

Author and political activist Mike Davis poses the question in

his book, Late Victorian Holocausts:

“How do we weigh

smug claims about the life-saving benefits of steam transportation and modern

grain markets when so many millions, especially in British India, died along

railroad tracks or on the steps of grain depots?”

(source: The

Observer - 'Late

Victorian Holocausts' By

Mike Davis

http://www.observer.co.uk/comment/story/0,6903,436495,00.html

http://books.guardian.co.uk/reviews/history/0,6121,424896,00.html).

A

Glowing account: How

an American Christian Missionary wrote about

British India

What has

England

done for

India

?

India

is no longer the prey of

Western ambitious powers. It is a solid part of the British possessions. It

knows, because it is a solid part of the British possession. It knows, because

it sends its troops that

England

cannot fight in a battle in

Europe

without its help. The expansion of education among all classes of people, the

physical care of the helpless classes, the subtle bond of the English language,

the development of the soil, the utilizing of the mineral wealth, the opening

of the country for the incoming of Western ideas, and greater than all

combined, the breaking down of all doors for the free spread of the Gospel.

England

has never achieved grander victories over

Waterloo

or

Quebec

than those which belong to her quiet and peaceful administration of

India

. The day has not yet dawned when it is possible to measure the whole magnitude

of

England

’s service to the millions of

India

. Generations must elapse before this can be done. When the hour does come, it

will be seen that the Englishman has never been wiser or more humane on the

Thames or that St. Lawrence than on the Ganges, the Indus, and the

Godavari

. The real fact is, not that he has conquered the country, but that he has

discovered it, and now governs it by as generous laws, and as even justice as

he rules over the millions within sight of his parliament at Westminster.

India

is no longer the prey of

Western ambitious powers. It is a solid part of the British possessions. It

knows, because it is a solid part of the British possession. It knows, because

it sends its troops that

England

cannot fight in a battle in

Europe

without its help. The expansion of education among all classes of people, the

physical care of the helpless classes, the subtle bond of the English language,

the development of the soil, the utilizing of the mineral wealth, the opening

of the country for the incoming of Western ideas, and greater than all

combined, the breaking down of all doors for the free spread of the Gospel.

England

has never achieved grander victories over

Waterloo

or

Quebec

than those which belong to her quiet and peaceful administration of

India

. The day has not yet dawned when it is possible to measure the whole magnitude

of

England

’s service to the millions of

India

. Generations must elapse before this can be done. When the hour does come, it

will be seen that the Englishman has never been wiser or more humane on the

Thames or that St. Lawrence than on the Ganges, the Indus, and the

Godavari

. The real fact is, not that he has conquered the country, but that he has

discovered it, and now governs it by as generous laws, and as even justice as

he rules over the millions within sight of his parliament at Westminster.

A

French scholar Barthelemy St. Hilaire, (1805

- 1895) in his book, “L’Inde Anglaise; son Etat Actuel son Avenir, has

written:

“Neither

in the Vedic times, nor under the great Ashoka, nor under the Mohammedan

conquest, nor under the Moguls, all powerful as they were for a while, has

India

ever obeyed an authority so sweet, so intelligent

and so liberal.”

England

has been a blessing to the

helpless continent.

England

has conquered

India

. But it has been less a conquest by steel and gunpowder than by all the great

forces which constitutes a Christian civilization.

(source:

Indika:

The Country and the people of India and Ceylon - By

Rev. John F Hurst p.

755 - 766).

***

In

Bombay, in famine camps, Sir A. P. Macdonnell,

President of the Famine Commission, reported, the people "died like

flies."

(source:

India

And Her People - By Swami Abhedananda

p.144).

Amitav

Ghosh author

of several books, The Circle of Reason (1986), won France's top literary award,

Prix Medici Estranger, and The

Glass Palace also

makes fun of the claim that the British gave India the railways.

"Thailand has

railways and the British never colonized the country," he says.

"In 1885, when the British invaded Burma, the Burmese king was already

building railways and telegraphs. These are things Indians could have done

themselves."

(source: Travelling

through time - interview with Amitav Ghosh).

Nick

Robins in his article titled "Loot" has said: "The

East India Company found India rich and left it poor."

And

for many Indians, it was the Company's plunder that first de-industrialized that

country and then provided the finance that fuelled Britain's own industrial

revolution." There was no increase in India per capita income between 1757

and 1947" In the beginning, Britain was buying cloth

made in India. In the end, India was buying cloth made in Britain, paying for it

not only with money but with the blood of its people. History teaches us that

history must never be forgotten.

(source: East

India Company - By Omar Kureishi )

According to Francois

Gautier: " The British did

impoverish India: according to British records, one million Indians died of

famine between 1800 and 1825, 4 million between 1825 and 1850, 5 million between

1850 and 1875 and 15 million between 1875 and 1900. Thus 25 million Indians died

in 100 years! (Since Independence, there has been no such famines, a record of

which India should be proud.)" (source: rediff.com).

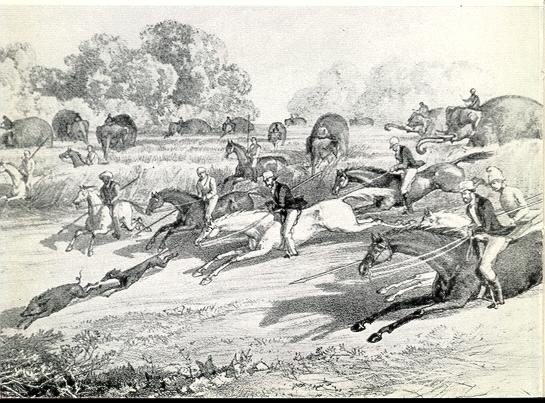

The

British hunting in India

***

Mrs Aruna Asaf Ali "

How can a civilized and enlightened people like the British have kept us so

backward and divided? They tried to educate a certain middle-class and allowed

it all the facilities; but the basic reforms they did not carry out. Our

literacy rates were so poor, and our technology has taken years to catch up with

modern developments."

(source:

Indian

Tales of the Raj - By Zareer Masani p. 130).

An English friend of India said,

"England, through her missionaries, offered the people of India thrones of

gold in another world, but refused them a simple chair in this world."

(source:

India

And Her People - By Swami Abhedananda

p.169).

William Samuel Lilly, in

his India

and Its Problems writes as follows:

"During the first eighty years of the nineteenth century, 18,000,000 of

people perished of famine. In one year alone -- the year when her late

Majesty assumed the title of Empress -- 5,000,000 of the people in Southern

India were starved to death. In the District of Bellary, with which I am

personally acquainted, -- a region twice the size of Wales, --

one-fourth of the population perished in the famine of 1816-77. I shall never

forget my own famine experiences: how, as I rode out on horseback, morning after

morning, I passed crowds of wandering skeletons, and saw human corpses by the

roadside, unburied, uncared for, and half devoured by dogs and vultures; how,

sadder sight still, children, 'the joy of the world,' as the old Greeks deemed,

had become its ineffable sorrow, and were forsaken by the very women who had

borne them, wolfish hunger killing even the maternal instinct. Those children,

their bright eyes shining from hollow sockets, their nesh utterly wasted away,

and only gristle and sinew and cold shivering skin remaining, their heads mere

skulls, their puny frames full of loathsome diseases, engendered by the

starvation in which they had been conceived and born and nurtured -- they

haunt me still." Every one who has gone much about India in famine times

knows how true to life is this picture.

Says Sir Charles Elliott

long the Chief Commissioner of Assam, "Half the agricultural population do

not know from one half year's end to another what it is to have a full

meal." Says the Honorable G. K. Gokhale,

of the Viceroy's Council, "From 60,000,000 to 70,000,000 of the people of

India do not know what it is to have their hunger satisfied even once in a

year."

(source:

India

in Bondage: Her Right to Freedom - By Jabez T. Sunderland p.

11-12).

Suhash

Chakravarty has brilliantly observed in his book, The Raj

Syndrome: "The vision of the Roman Empire did not merely inspire the

Raj. It was universally claimed that the Raj was the inheritor of the political

and cultural legacy of Rome. This was characterized by

snobbery, ruthlessness, and intolerance which were given the nomenclature of

patriotism, loyalty and fortitude. Economic benefits were dressed in idealist

garb, mercenary motives in a moral crusade and romance and adventure camouflaged

political and military aggression.

As a substitute to Greek and

Roman theatre, the American films arrived – early Christian films complete

with gladiators and lions, those of Tarzan and the Apes, the ‘westerns’ with

trigger-happy cowboys chasing the feathered Indian, followed by the urbanized

‘westerns’ where cars replaced horses and ‘cops’ replaced cowboys. The

impact was remarkable because the attempt had been to reduce the quantum of

wisdom and wit to the minimum. Superimposed on this was

the idea of the ‘chosen people’ operating on the doctrine of Christianity.

God was supposed to back only the Christians. Christianity was offered as

synonymous with science which was called service and service was the other name

for sharp shooting guns."

(source: The

Raj Syndrome: A Study in Imperial Perceptions - By Suhash Chakravarty.

Penguin Books. 1991 193).

Page < 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 >

|